Words by Joe Rogers

When life gives you apples

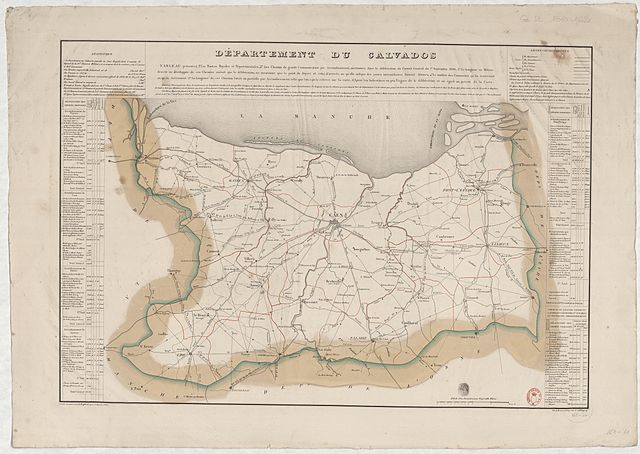

The department of Calvados is about three hours west of Paris and six hours south of Portsmouth. It contains talented cows responsible for the world’s best butter, the historical tapestry hot-spot of Bayeux and roughly three million apple trees.

Normandy wasn’t built to be wine country. A few houses in the region persist at viticultureand see good results, but vines tend to struggle there – the summers are too short and the coastal winds are too intense for widespread winemaking. However, the Normans don’t let this stop them from having a good time. The humble apple, being made of sterner stuff than the grape, has thrived in the region for centuries – particularly in the central department of Calvados.

Following the universal truth that human beings will ferment anything they have handy in the pursuit of getting merry, Calvados has become synonymous with the brewing of cider and the distilling of apple brandy. Broadly speaking, these brandies are made by distilling fermented apples and pears to create ‘eau–de-vie de cidre’ which is then aged in French-oak casks prior to bottling. Over time, the Calvados region has acquired three distinct geographical designations, or AOC, for its brandies, which are enjoyed throughout France and shipped all around the world.

Appellations

Each of Calvados’s three sub-regions has its own particular growing conditions and regulations that affect the character of its fruit, cider, and brandy. The best-known of the three is AOC Calvados, which extends all across the wider region, and the produce of which accounts for around 70% of all Calvados sales. In the heart of the region, we find the tightly controlled Pays d’Auge where high-grade, top-shelf Calvados is made using only traditional copper pot stills. These brandies are prized for their richness and long aging potential. Finally, the Domfront in the south-west was granted an AOC in 1997 to honour its traditional connection to the apple’s close cousin, the pear. While pears can be included in the mix when making Calvados – not more than 30% in the case of the Pays d’Auge – Cavlados Domfrontais must comprise at least 30% pears. They tend to be fruity spirits that reflect the freshness and perfume of their raw materials. If producers cultivate fruit in one of these designated areas, make brandy to strict specifications, leap through dozens of regulatory hoops along the way and have their product approved by a government tasting panel – only then can they call themselves makers of AOC Calvados. It’s a long journey, the first step of which happens in the orchard.

Fruit

Your average cider apple or perry pear won’t make particularly good eating. They are however full of juice and highly aromatic, which means they’re perfect for distilling. A single estate will often grow a dozen or more varieties, all genetically distinct, and with their own particular qualities. Walk through the trees in the Pays d’Auge and you might find bright red Binet Rouge, citrussy Pèpin Doreè and sour Petit Jaune, along with any number of more than 200 permitted types. This diverse range of fruit is divided into four categories that form the building blocks of Calvados. Sweet or ‘douce’ apples bring the sugars that fuel fermentation, while acidic ‘acidulèe’ fruit lowers the PH and aids conservation of flavour. Bittersweet ‘douce-amère’ and bitter ‘amère’, the so-called phenolic varieties, supply the tannin that gives structure and body to eau-de-vie. By drawing on a diversity of fruit across these four categories, producers create layers of flavour in their final product. Selecting seeds, planting orchards, waiting years for trees to reach maturity, and caring for fruit as it grows are all part of making Calvados.

Cider

As the summer in Normandy draws to an end, houses across the region will begin to harvest their fruit, targeting individual varieties as they reach ripeness. It will take about 18kg of apples and pears to produce a single litre of Calvados, so the work involved is considerable. Once picked, sorted and washed, fruit is traditionally packed into wooden boxes and left to rest somewhere dry and cool. After losing a little weight to evaporation – and gaining a little flavour through extra ripening – the fruit is ready to be processed.

First, the fruit will be crushed or shredded, macerated briefly and then pressed to extract the juice. This fresh juice – known as ‘must’ – contains flavour from every part of the fruit; skin, flesh, and core. At this point the natural yeasts present on the fruit and in the air will already be consuming sugars in the must and producing alcohol. Next, the must is filled into large oak barrels called ‘tonneau’ for further fermentation, at which point additional yeast can be added, but otherwise things are left pretty au naturel. The Pays d’Auge AOC requires a minimum of six weeks’ fermentation, though producers may choose to leave the process running through winter and into the following year. As the yeasts work and fermentation progresses, new chemical compounds are formed that correspond to flavours and aromas, bringing ever more complexity as time goes on. The resulting cider is bone-dry and cloudy, filled with tiny particles of fruit and spent yeast. According to the rules, the cider cannot be sweetened or pasteurised and must have an alcohol content of at least 4.5% – though the average is around 7%. The most meticulous Calvados producers will even go to the lengths of aging their cider in casks before they send it to the still house, sometimes for years, all in the name of flavour.

Eau-de-Vie

Distilling in Calvados begins in the autumn. Across the majority of the region you’ll find continuous-distillation column stills capable of extracting high-proof alcohol from large volumes of cider without stopping. While some bigger producers employ large, modern column stills – which bear resemblance to those used to make gin and vodka – the majority of the 100-or-so columns in the region are small, rustic setups. Some are even portable, staffed by itinerate distillers who travel between estates, like those found down in Armagnac. The two-column still is cheaper and easier to run than the traditional pot still and produces a lighter, cleaner style of spirit. For this reason, it is favoured in the Domfrontais, where capturing the delicate characteristics of the pear is key. In the strict Pays d’Auge, however, only the alambic traditionnel a Calvados is permitted.

These copper pot stills follow the same basic design as the alambic Charentais used in Cognac. In this arrangement, warm cider flows into a copper pot and is heated from beneath by direct fire – gas or, more traditionally, wood – causing the alcohols in the cider to vaporise and travel through a tube evocatively called the col-de-cygne (swan’s neck) and into a spiral of copper tube suspended in a tank of water. The cool water in the tank causes the vapours to cool and condense into a clear liquid of about 30% ABV, known as ‘petit eau’, which is then distilled a second time to a higher strength of between 60% and 72% ABV. The intensely flavoursome spirit that runs off the condenser after the second distillation is called eau-de-vie de cidre, the nascent form of Calvados. The region’s regulations stipulate that all distilling across Calvados must be completed by May. After this time the year’s eau-de-vie will all be filled into oak casks, ready for maturation, watched over by the cellar master.

Oak

The maitre de chai (cellar master) will have a preferred tonnellerie (cooperage) that supplies casks to suit a Calvados house’s particular needs. For the cooper, this will mean sourcing mature oak trees in forests across France. Felled trunks are split into staves which are left to dry and season in the open air for about three years, during which time bitter tannins in the wood are broken down. These staves are then formed into barrels, which are toasted inside, preparing them for filling with new eau-de-vie. Climate, soil type, planting density and other matters of terroir are said to affect the structure and chemistry of the wood, meaning that casks from different origins will make their own individual mark on the spirit inside them as time passes. Likewise, the level of toast requested by the cellar master will affect maturation hugely. A light toast might produce sweet aromas of vanilla and nuts, while a heavier toast will imbue spirits with a greater level of sweet spice and tannin. Here, as at every stage of the process, choices are made that will impact the profile of the finished Calvados.

Time

It is common practice to fill young eaux-de-vie into new oak casks that are fresh from the cooperage and full of flavour. The initial maturation period is quite intense as the spirit absorbs lots of soluble compounds from the fresh oak, becoming darker and richer in the process. The tannins and other substances imbued into the spirit during this stage provide essential structure and texture. However, too much contact with new oak and the original fruit character of the eau-de-vie will be lost, overwhelmed by wood influence. For longer maturation, the cellar master will transfer the contents to older, sometimes larger casks, for further ageing. Some cellar masters will also introduce casks previously used to age cider, wine, or other spirits to add more elements to their creations. After two years – or three in the Domfrontais – producers may submit their brandy for appraisal by the mandated tasting panel. Only if they pass muster may they be sold under the appropriate AOC.

After three years in cask, lots of Calvados will still be considered young, with many years left before it reaches the peak of its maturity. Over time, it will undergo a number of physical and chemical changes; reducing, evaporating, and oxidising. The alcohol content will steadily decline and the florals and freshfruit notes detectable in young Calvados will gradually give way to more mature flavours of dried fruit and spice. In time, aromas of chocolate and coffee might appear, as well as hints of leather and tropical fruit; notes known collectively as ‘rancio’.

Blending

Producers will sometimes bottle the contents of a single, exceptional cask as vintage Calvados, stamped with its year of distillation. The vast majority of casks in Normandy, though, are destined to become components in blends. In a well-stocked cellar there will be young eaux-de-vie that taste of blossoms and fresh fruit, others that are rich and tannic, and some that are old, deep and dark. The skill of the blender is to look at these casks not as discrete entities, but as elements of something layered and complex that just need to be introduced to each other.

Age classifications described in Calvados regulations give us an idea about the level of maturity to expect in a blend: Calvados labelled ‘three star’, ‘VS’ or ‘Fine’ will comprise brandy aged for at least two years, a threshold that raises to three years for ‘Vieux’ Calvados, four years for ‘VSOP’ or ‘VO’ and six years for ‘XO’ and ‘Hors d’Age’. Within these minimum requirements, the cellar master is quite free to combine brandies of different ages to create depth and balance, marrying them in large oak vats before bottling. Producers outside the Pays d’Auge may also choose to combine lighter columnstill eau-de-vie with heavier pot-still eau-de-vie to create a spirit with the desired characteristics of both styles – a practice common in the whisky and rum industries.

Most of the Calvados on our shelves is bottled at around 40% ABV – the legal minimum strength. Some of the spirit’s alcohol content is lost during maturation, with further reduction carried out by the addition of water or, in some cases, old, underproof eau-de-vie.

serving

Unlike Cognac, which is largely exported, the majority of Calvados is enjoyed in France. A café calva, in which a little shot is taken with coffee, is a traditional way to kick off the working day in the north. Calvados is also taken as a palate cleanser, sometimes with sorbet, to punctuate the end of one course before the beginning of another – the so-called trou normand. Those with fruitier elements and a bit of zip to them cut nicely through cheeses like the Normandaise delicacies Camembert and Livarot – a wonderful bit of flavour synchronicity, as the traditional ‘high-stem’ orchards of the region are planted with space among the trees for cows to graze, so that brandy and cheese can be made on a single estate.

Older Calvados is a natural friend of deeper flavours like chocolate, making it a great way to close out a meal. You can pick up long-aged or vintage Calvados for relatively modest sums, making it a spirit that affords great opportunities to drink a little history. A bottle sealed decades ago won’t have changed very much, if at all, and should still have a sense of place about it; every sip containing fruit, oak and time.