Words by Joe Roger

‘Everything is noble in Cognac and everything is worth trying.’ Those words of wisdom are from Amy Pasquet, interviewed elsewhere in this guide with her husband Jean about their organic single-estate Cognacs. ‘We make really good eaux-de-vie here in Grande Champagne, but there’s good eaux-de-vie being made everywhere.’

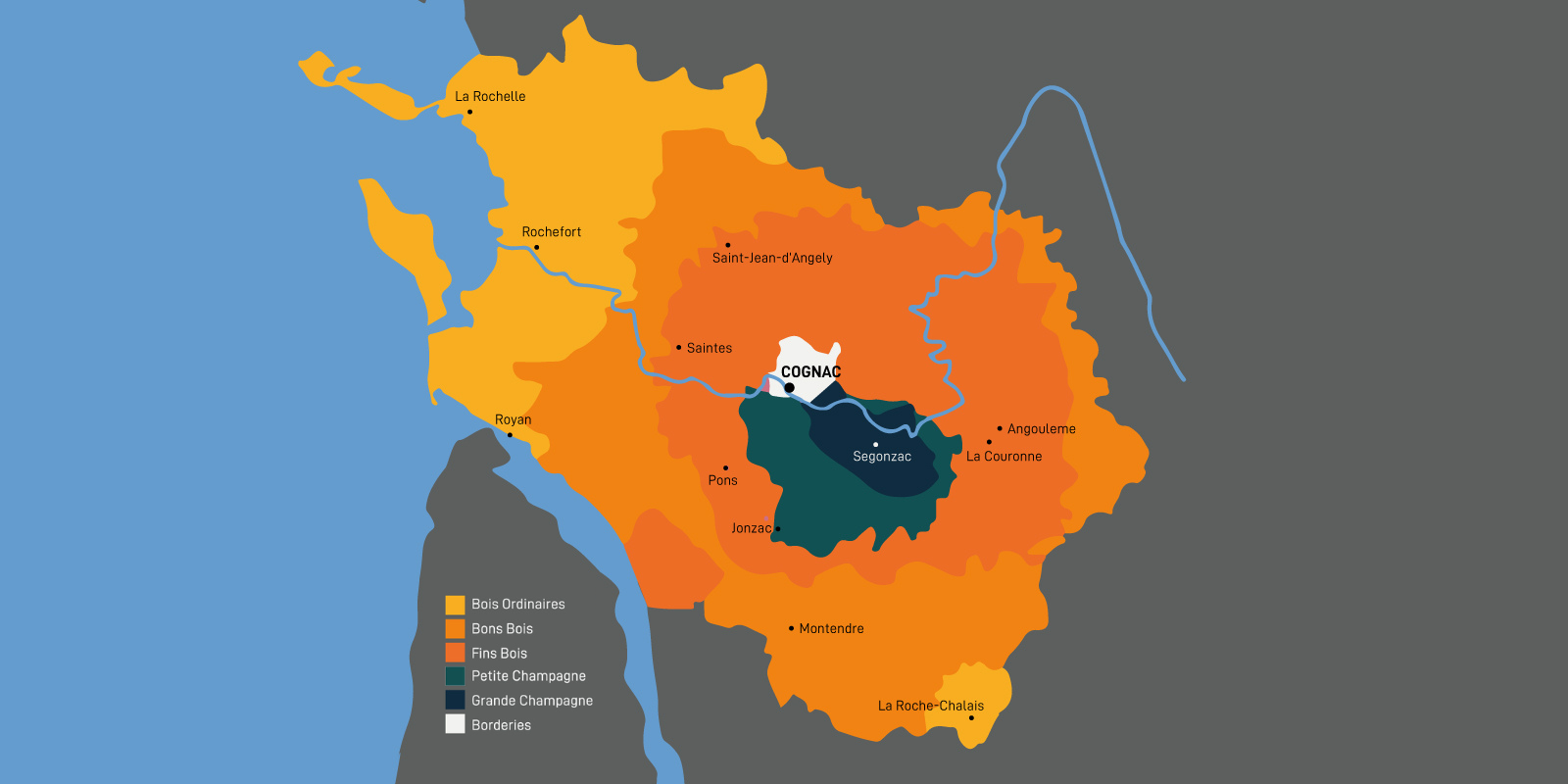

Cognac from Grande and Petite Champagne has always been thought of as exceptionally high quality. Open any book on the subject and you’ll find much written about their elegance and long-ageing potential. Borderies, to the north of the Champagnes, is also held in high regard, with Martell and Hennessy buying the majority of the region’s output to fold its reported floral, nutty character into their blends. But beyond that, the big houses tend to avoid – or avoid discussing – any purchases of wine or eau-de-vie from the outer regions.

This has given rise to the idea that Champagne Cognac is the absolute gold standard. However, an increasing number of houses are promoting exceptionally good brandies from the Fin Bois, Bon Bois and even the unflatteringly named Bois Ordinaire.

‘There are very bad Grande Champagne and there are very good Bon Bois,’ Jean adds. ‘We have a programme where we select casks from other vintners and sometimes Cognac from the Fin Bois will just blow our minds. It’s said that Fin Bois are not supposed to be aged super-long, that they’re better young, but I just don’t think there’s any truth to that. What we’ve realised is that the map of the crus is probably not well drawn. The Fin Bois and Bon Bois are too large to be all the same, it’s just impossible.’

The boys from the bois

Inspired by my conversation with the Pasquets, I approached Stéphane Roudier, commercial director of Cognac Vallein-Tercinier to discuss preconceptions around Cognac’s different terroirs. This small house’s bottlings from across the Bois were a great hit at Cognac Show 2022, so he seemed the perfect person to talk to.

My first question for him: are eaux-de-vie from the grand crus inherently superior?

‘This is just not true,’ he says assuredly. ‘Eau-de-vie from Fins Bois or Bon Bois has the same ageing potential as the Champagnes. For each one, it depends on the quality of the eau-de-vie and especially on the way the ageing has been managed by the cellar master. We call this “the art of ageing”. A few years ago, we bottled a Bons Bois Cognac with 80 years of ageing in casks, the Lot 40 Hommage, which was surprisingly fresh and pleasing to the taste.’

This long-since sold out bottling received a score of 90/100 from legendary taster Serge Valentin on the indispensable Whisky Fun. While one example is not enough to refute the canard that Bon Bois Cognac is of inherently lesser quality, this is one of many such bottlings Vallein-Tercinier has produced over the years. They’re also not the only house finding treasure in Cognac’s overlooked outer reaches.

The illustrious Cognac Prunier has in recent years put its name to many vintage eau-de-vie originating from small growers across the region. As has up-and-coming bottler Fanny Fougerat, many of whose Cognacs showcase the poise and elegance to be found in the Fin Bois. The fifth largest house in the region, Cognac Camus, has always been a standard bearer of the Borderies, but its Île de Ré series takes us to far-flung vineyards planted in the sandy, calcareous soils of the Bois Ordinaire. These unusual Cognacs, with their honeyed sweetness and delicate maritime character, show us a side of the region that’s rarely seen internationally until now.

Eaux-de-vie originating near the coast has historically been dogged by the suggestion that it carries a salty, even iodine-y, hint of the sea. But perhaps that’s only a problem if you want all Cognac to taste one way. You don’t have to sample many of these outlanders to get the feeling that the big three crus at the centre of Cognac are not necessarily the pinnacle. They may well be delicious, but they don’t have to be the only type of delicious available to us.

With this in mind, I return to Jean Pasquet’s suggestion that the relationship between the crus of Cognac and the nature of the eau-de-vie produced there may not be as clear as we think.

Redrawing the map

The map of the Cognac region as we know it is based on a decade-long survey carried out by geologist Henri Coquand in the mid-19th century. His extensive study – the first of its kind to be carried out in a wine-producing region – identified distinct crus with their own terrain and soil types.

The lines Monsieur Coquand sketched out were re-drawn many times over the years as growers, merchants and state officials made attempts to classify the region. Various communes were traded between sub-regions and different crus were suggested. The Bois Communs, Premier Bois, Champagne de Bois, and many others all came into being and were deleted. In 1936, after decades spent cementing the essential nature of Cognac, we were left with the six sub-regions recognised today.

At the heart we have Petite and Grande Champagne, covering thick deposits of chalk formed during the Late Cretaceous period. The particular soil found in the Champagnes would be difficult terrain for growers hoping to make rich, round wines for the table. But it is ideal for making the low-ABV, low-PH white wines that are a gift for the distiller.

However, as Stéphane is keen to point out to me, this is not the only place in the Cognac region that these growing conditions are found. ‘Some parts of the Fin Bois and Bon Bois are better to produce Cognac than others, with clay and limestone in the soil – parts with only clay in the soil don’t produce good wines for distillation.’ Conditions in these areas may not be identical to the top crus, but this may just mean variation in the character of their Cognac as opposed to its quality.

‘The outer region is thought of as inherently inferior because it’s not so publicised. There are big luxury brands based in the Champagne area and only they can spend money on marketing and advertising. So, everyone hears and reads about “Grande Champagne, 1er Cru du Cognac” and they think it’s the best.’

This raises an interesting point about the history of the region. In truth, it wasn’t just good soil and a cool climate that gave Cognac the edge over other brandies. One of the other advantages that it had – particularly in its early days – was a thriving merchant class with a tradition of international trade.

Long before the first stills arrived in the region, the Charentais dealt in goods like salt, wine and paper. The nearby port of La Rochelle allowed for the creation of trade routes that linked Cognac to the world. When distilling started to gain momentum in the region, the nascent industry was able to follow the paths established by previous generations to take its brandy to market in Britain, Ireland, the Low Countries and further afield. It was inevitable then that the most successful merchants would headquarter themselves in the magnetic centre of the region, and extoll the virtues of the brandies derived from the surrounding vineyards.

The spice of life

We see here how the concept of the inner crus as superior may be a matter of economics and marketing as much as geography. This is not to say that the quality of Champagne Cognac is necessarily overstated. It merely suggests that the wider region might offer variety rather than a sliding scale of quality.

‘Really, each cru has its own typicity,’ Stéphane explains. ‘Fins Bois for the tropical fruits and candied fruits that make it so easy to drink; Borderies for the florals and the finesse; and the Champagnes for complexity and the longer finish ideal for after dinner. Really, you should have one bottle of each at home.’

This is sound advice and could well be applied to any distilling tradition. Speyside may be home to some of the most famous names in Scotch whisky – your rich, powerful Macallans and Mortlachs for instance – but their existence doesn’t mean there isn’t room on your shelf for a smoky, minerally single malt from Campbeltown. Likewise, Jamaican rum is beautiful stuff but appreciating it doesn’t mean turning a blind eye to the virtues of a light, dry Cuban aguardiente. In Cognac, as in all things, it pays to embrace variety.