Words by Joe Rogers

The last weekend in May 2016 saw hailstorms destroy grapes on the vine across Chablis, Beaujolais, and Cognac. Some vineyards lost entire crops as 15 centimetres of hail fell in just 15 minutes. Weeks earlier, 194 state representatives had signed the Paris Agreement, signifying a global effort to combat the impending climate crisis.

what is to be done?

In France, as in other parts of the world, the need for such an agreement was already being felt. These disastrous showers of hail followed warm summers in 2014 and 2015 which had brought harvests forward by as much as three weeks. Further storms in 2018 damaged as much as 10,000 hectares of vines across the Charente. It was becoming increasingly clear to the people of Cognac that action was needed.

Crops ripening a few weeks ahead of schedule might not sound like much. But for Cognac production it can be ruinous. To make good eau-de-vie, a wine with a low ABV and high acidity is essential. When grapes ripen earlier in the year, the character of this delicate white wine is threatened in a number of different ways. Overripe grapes mean sweeter wines with higher alcohol content and lower acidity – calamitous for the distiller and sure to produce poor quality eau-de-vie. Higher air temperatures also increase the risk of fermentation beginning before grapes are pressed, introducing undesirable aromas to the wine that will be intensified during distillation. There’s also the threat that late summers will cause wines to oxidise before they reach the still house, further tainting the end product.

Cognac evolved where it did for a reason. It’s the culmination of numerous biological, cultural, and environmental factors particular to the region. When one of these elements begins to change, the character of the spirit itself comes under threat. Growers may do as the Australians do and pick their grapes at night, when the air is cooler, to preserve their freshness. They might raise hail nets to protect their vines and even employ cloud seeding techniques to break up harsh weather fronts as is practiced in Bordeaux. However, such measures will not solve the problems posed by rising temperatures. Luckily for the region, and for Cognac lovers around the world, efforts are underway to meet the challenge head on.

Lessons from history

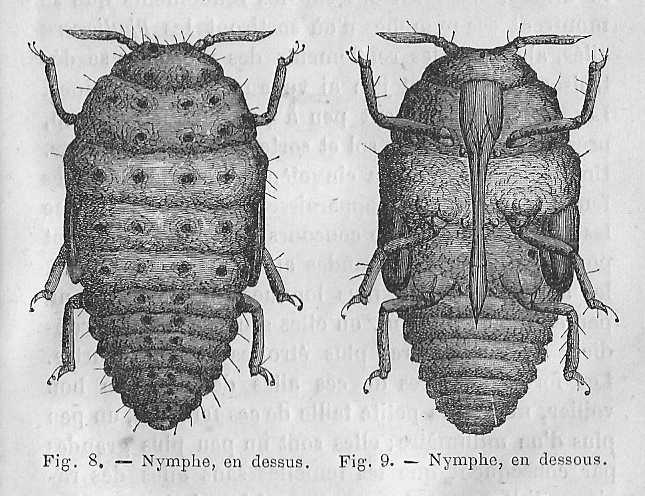

Climate change is not the first ecological crisis to befall Cognac. When the invasive phylloxera aphid arrived in the Charente in the 1870s it all but wiped out the region’s viticulture. The Folle Blanche and Colombard grapes that supplied its stills at the time proved particularly susceptible to the blight and by the end of the decade some 80% of all stock had been destroyed. Station Viticole was formed in 1892 to help growers graft their vines onto phylloxera-resistant roots from North America. The organisation also helped in planting of large quantities of Ugni Blanc, known as Trebbiano in its native Italy, which would help reverse the fortunes of the beleaguered region. It’s a relatively hardy grape, offering good yields and late maturation. Mediterranean varieties like this are perfect for distilling because they’re adapted to warmer climes and so mature more slowly in the mild conditions of southwest France. At least that has been the case historically. Today, Ugni Blanc accounts for 98% of all Cognac production. However, rising temperatures may mean its time is coming to an end.

For Alexandre Gabriel of Maison Ferrand, the devastation of phylloxera holds lessons for the current crisis. ‘At that time, the grape varieties and their rootstock had to be rethought with this new element. Now with global warming, we are studying which grape variety would be the most suited to preserve the beautiful and unique taste of Cognac.’ Across the region, the race is on to find varieties that are slow maturing and supply the much-needed acidity. ‘We need a sturdier grape variety, resistant to disease. We are experimenting with Folignan, which is a cross between Folle Blanche and Ugni Blanc, two historical grape varieties of the Cognac region. We at the BNIC and Station Viticole are researching new varieties with the goal in mind of preserving the taste and aromatic profile in Cognac and adapting to climate change.’ Many houses are planting historically overlooked grapes and even developing new hybrids with a view to futureproofing production.

It’s likely that in years to come we will see changes to the Cognac appellation, with rules being altered to accommodate the swings in temperature. While some winemakers are able to chase ideal climates around the world, planting in regions once considered inhospitable, Cognac is inextricably tied to its terroir – so the map of the delimited area is unlikely to be redrawn. There is also little desire among producers to introduce measures that would compromise the character of their spirit – adding sulphur to preserve their wines prior to distilling, for instance. As such, the inclusion of grapes outside of the six varieties currently permitted is likely to be the next big change. Hine and Rémy Martin are already planting a few hectares of light-skinned Monbadon a year in the hope that it will succeed where other varieties fall short. Results are said to be promising, but not yet conclusive.

Alexandre also believes that advances made in Cognac production must be part of a wider effort to be ecologically sound. ‘The négociants are working very hard on the sustainability of Cognac,’ he says. ‘Together, we have defined the Certification Environmentale Cognac (CEC) - which is an environmentally-friendly way of producing Cognac - with the goal of having everyone follow these standards by the year 2028.’ Maison Ferrand’s great patriarch Elia Ferrand the 8th was himself a great proponent of organising growers and négociants to safeguard the quality of Cognac, something that informs Alexandre’s push for sustainability. ‘At Ferrand we are working on lighter bottles, as well as working towards using 100% recycled glass. Together with our colleagues, we are studying transport solutions favouring electric railroad systems rather than trucks. We are also now using zero herbicide at Ferrand. As an industry we are exploring ways of using much less energy for distilling.’ The struggle to preserve Cognac, it seems, will be fought on many fronts.

the long road ahead

These efforts are representative of a broader move toward sustainability across France. The Haute Valeur Environmental was developed by the French Ministry of Agriculture in 2001 to promote sustainability in farming and viticulture. The three levels of certification it offers to producers cover matters of water management, bio-diversity, and the use of pesticides. So far, more than 2,500 growers in Coganc have attained certification. This accounts for more than half the region, but the BNIC hopes that by 2030 it will see 100% HVE compliance.

In the coming years, the Cognac industry will have to perform a difficult balancing act. It must adapt production to compensate for climate change, and make it environmentally friendly, and economically sustainable, all while preserving the essential Cognac-ness of Cognac. Doubtless, there are difficult challenges ahead. But if history has proven anything of the Charentais, it’s their resilience.