Words by Joe Rogers

The river Charente, which flows from Hute-Vienne to the Atlantic, makes Cognac production possible. It’s cooling influence on the region’s vineyards helps to grow grapes ideal for distilling, while the humidity it brings fosters the perfect conditions for aging spirits.

Water of Life

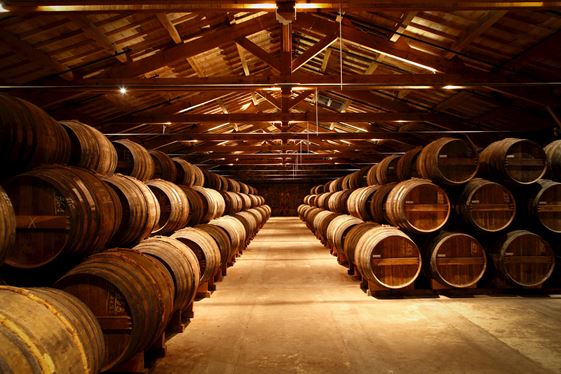

When merchants cut their cellars into the limestone of the Charente basin, way back in the early days of the Champagne brandy trade, they were making use of the river’s natural ability to regulate temperature and humidity. They might not have known it at the time, but those perfect maturation conditions were one of the things that gave Cognac the edge over other brandies.

Atmospheric factors have an enormous impact on the way a cask of spirit develops over time. The numerous chemical and physical reactions that take place between eau-de-vie, air, and oak will make or break a Cognac and must be carefully managed. Long-standing Cognac house Rémy Martin maintains 30 separate cellars, or ‘chai’, on its estate in the centre of the region. They are constructed the traditional way, with thick limestone walls to regulate temperature and no artificial means of climate control. Unlike other appellations, where regulations specify cellars must be built underground, the rules of Cognac allow for aging above ground as well as below. Both have their advantages. ‘What we want is for the cellar to follow smoothly the rhythm of the seasons; cooler in winter time, warmer in summer time,’ says Rémy Martin cellar master Baptiste Loiseau. By providing conditions that aren’t too vulnerable to swings in temperature and the shock of changing seasons, Loiseau can predict how eau-de-vie will evolve over time, allowing him to plan effectively for the future. ‘The impact of location, climate, and hygrometry (presence of water vapour) is all-important. In order to recreate our blends year-after-year, I have to know the characteristics of each eau-de-vie and each cellar’, he says. As Baptiste points out, there are a number of factors that decide the personality of a given cellar, but broadly speaking they are divided into two categories; dry and humid.

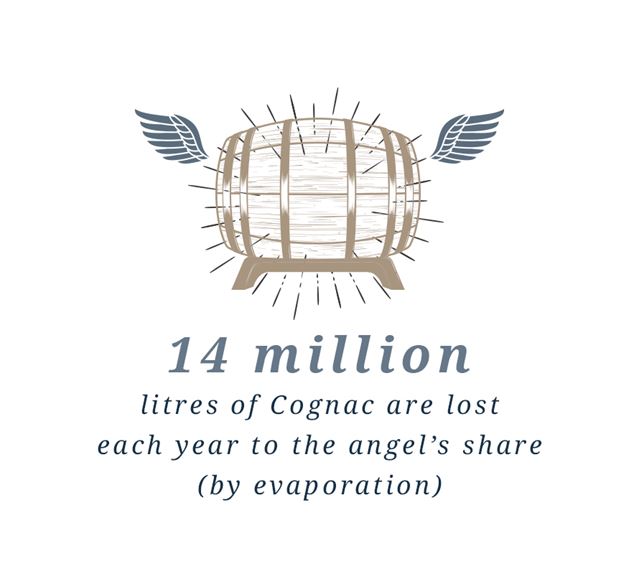

A dry cellar will remain between 40-60% humidity throughout the year, whereas a humid cellar will consistently hover around 90-100%, meaning that the air in a humid cellar will contain about as much moisture as it possibly can at a given temperature, and a dry cellar roughly half that amount. Oak casks allow gasses to escape into the air without letting liquid leak all over the floor – it’s the miracle property that makes aged spirits possible. In a humid environment, water will evaporate from eau-de-vie slowly as there’s just not much room for it in the air, and alcohol will evaporate relatively quickly. As a result, ABV declines over time and spirits get gentler, softer, and altogether more polite. In dry cellars the opposite occurs; water disappears, alcohol content remains high, more compounds from the oak are absorbed, and spirits become spicy, dry, and intense.

Playing the Long Game

For the cellar master, access to different ageing conditions means more variety in their stock. Loiseau describes this as having ‘a large palette of eau-de-vie for me to select from in order to make a harmonious blend.’ In pursuit of as many diverse flavours and aromas as possible, the cellar master will often shift eau-de-vie from one location to another to layer it with different characteristics. ‘We do not keep eau-de-vie in one cellar throughout its ageing or even in the same barrels. It might be aged in different generations of barrels and transferred from one cellar to another depending on the conditions and the characteristics of the blend I want to create’, he explains. By keeping it moving, a cellar master can cultivate, tweak, and engineer their Cognac as it matures. Sometimes, however, it pays to use a light touch.

There are barrels at the Rémy Martin estate containing eau-de-vie of 100-years-old. ‘A cellar that’s not too dry and is without extreme variation in temperature is ideal for ageing eau-de-vie in a long-term vision. The barrels are not resting directly on the floor, nor too close to the walls, to allow good breathing conditions,’ says Baptiste. ‘To age our very old and rare Cognacs we have a few cellars that have the perfect conditions. One of them is the chai Andre Heriard Dubreil, from which we recently bottled a unique limited-edition blend called Louis XIII Black Pearl AHD. It is a truly incredible Cognac which opens with a burst of fresh, floral, and earthy aromas. With a little time, you can feel the evolution of flavours. The unmistakable woody notes are evocative of the century old tierçon barrels in which it was aged and the cellar from which it was extracted.’

For cellar masters like Baptiste their chai are not merely storage; each one is indicative of a style, a profile, a set of flavours at their disposal. In expressions like this unusual Louis XIII we see how important they are in shaping the character of Cognac. While £14,500 a bottle might be a little steep for some of us, there’s lots of scope for other releases that explore this aspect of Cognac production. Will we see more single-cellar releases from Rémy Martin? ‘Perhaps,’ says monsieur Louiseau – with the air of someone who knows he’s working on something good.